Drawing twice

At the very start of the year, Hockney makes a photographic collage of Ann Upton, David Graves, and his mother caught at various moments—variously lost in thought—over a game of Scrabble. In February, in Japan to speak at a conference about paper in art, he takes photographs, turning them into photographic collages when he returns to England.

Walking in the Zen Garden

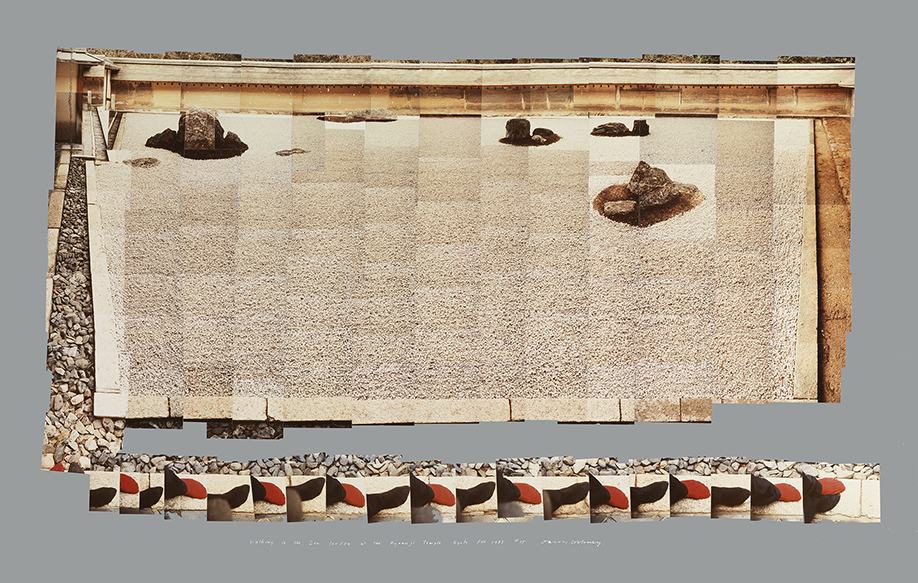

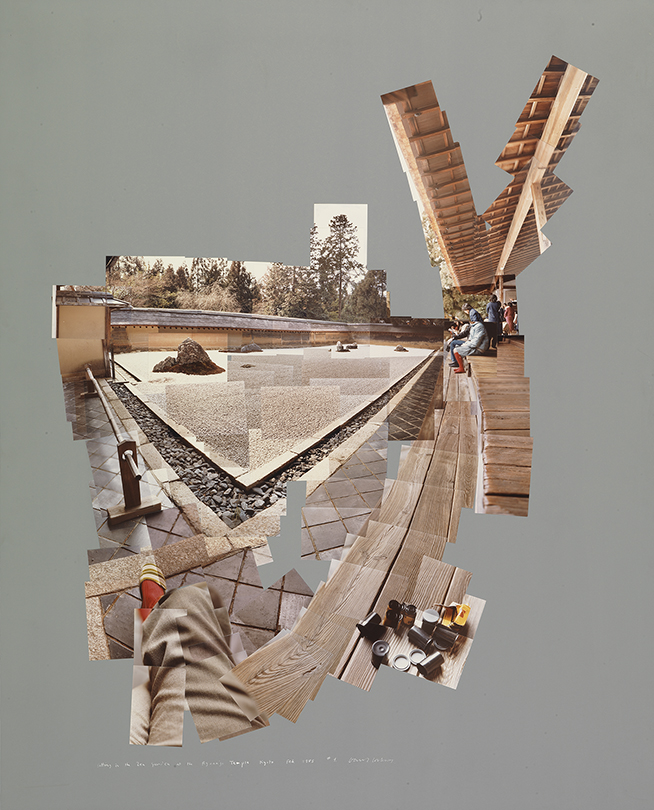

To compose a picture of a fifteenth-century Japanese rock garden, Walking in the Zen Garden at the Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983, [NESTED]Hockney applies obsessive concentration to collaging a field of pebbles: “I had to count and really look at those pebbles to link one with another.” Hockney’s own feet appear walking across the bottom of the picture plane—upending the fixed-point perspective of the observer in Western art.

I began looking at photography from various points of view. They said perspective was built into the camera. But my experiments showed that when you put two or three photographs together, you can alter perspective. The first picture I made where I felt I had done that was in Japan where I photographed Walking in the Zen Garden at the Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983. I made it into a rectangle by moving around myself and taking shots from different positions, whereas any other photograph would show it as a triangle .... I was very excited when I did that. I felt I made a photograph without Western perspective. It took me a while. I didn’t know much about Chinese art, even when I went to China. The photography I did took me to Chinese scrolls.

Studying Chinese scrolls

Hockney becomes engrossed in Chinese scrolls, in large part because they offer an alternative to the Western approach to perspective. [NESTED]He spends considerable time studying them at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and at the British Museum in London, and reads Principles of Chinese Paintings (1959) by George Rowley, the founder of Princeton University’s studies in Far Eastern art.

It was an attack on perspective—it was all about the spectator’s being in the picture, not outside it—an attack on the window idea, that Renaissance notion of the painting’s being as if slotted into a wall, which I’d always felt implied the wall and hence separation from the world. The Chinese landscape artists, with their scrolls, had found a way to transcend that difficulty. In my own photocollages, some of the ones I’d done on my trip to Japan earlier that year, I’d been pushing the notion of the observer’s head swiveling about in a world which was moving in time, but I’d really only just begun to try and deal with how to portray movement of the observer’s whole body across space. And that’s precisely what these Chinese landscape artists had mastered, according to Rowley.

A lecture, “On Photography”

Hockney, more and more preoccupied with the challenge of representing different moments in time as another aspect of multi-perspective image-making, delivers a lecture in November at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which argues for a multi-viewpoint and multi-temporal approach to photography, to better reflect the lived human experience.

I made pictures of a walk in a Zen garden where I attempted to show the experience of walking, so that one might see the entire experience, in time. It means that you must look with your memory. Then it led me to believe that we’re always looking without memory .... I came to the conclusion that there is no such thing as objective vision. There never can be, because even the memory of the first instant of looking is then part of the perception, and it adds up and it adds up. It brought me closer to the way we actually experience the activity of seeing, and it actually led me back to drawing and painting, with a whole new sense of the possibilities to be found there.

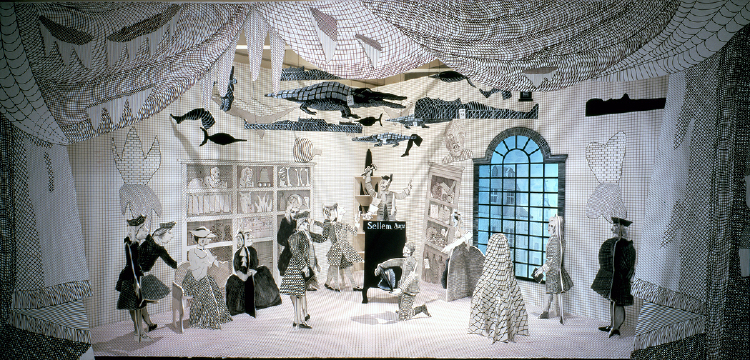

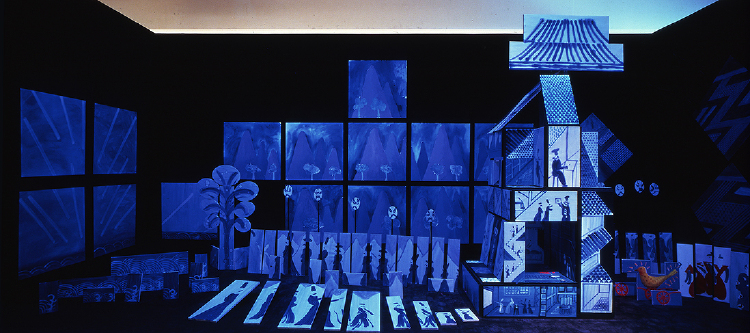

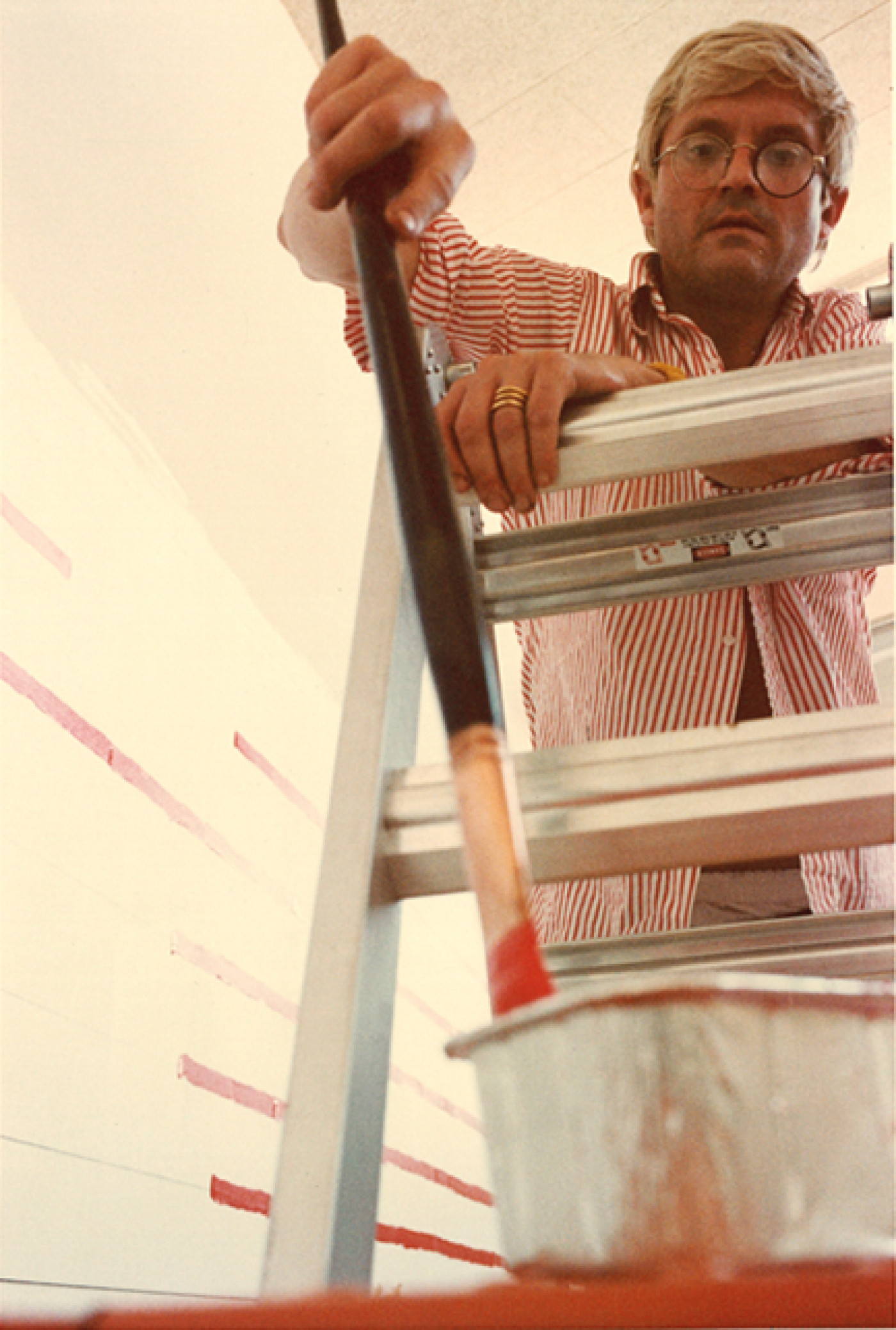

Hockney Paints the Stage

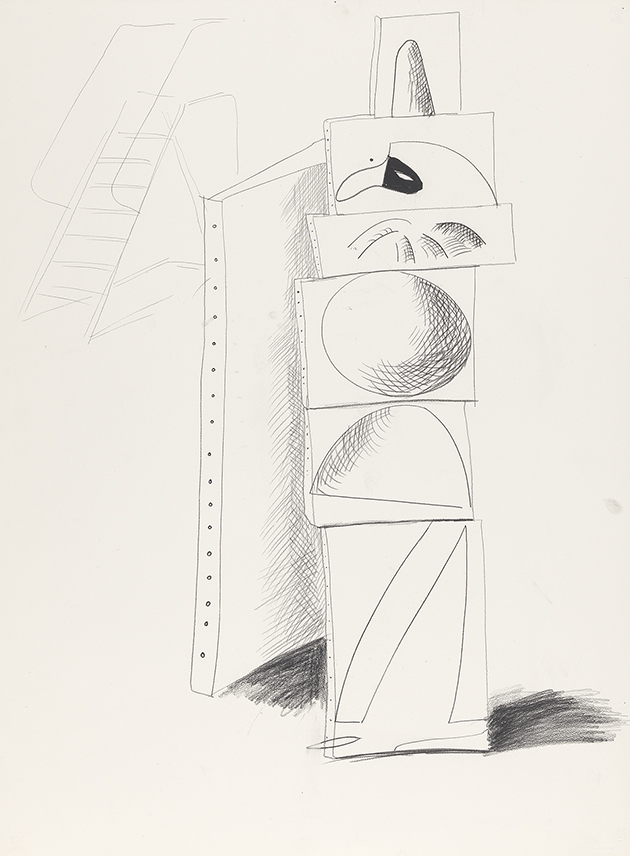

For the exhibition Hockney Paints the Stage at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, planned as an exhibition of his theater design sketches and models, Hockney decides new works must be made. He builds nearly full-scale tableaux of select scenes from past productions, which are, in some cases, fresh departures. When the exhibition travels to London, John Russell Taylor notes in the Times that the work shows “brilliant and unflagging inventiveness to be sure, but also every evidence of the blood, sweat and tears which must have gone into the creation of these apparently effortless designs.”

Theatrical design is about creating different kinds of perspective, but the perspectives can’t be quite real in the theater, because they have to be made in such a way that they create an illusion. That’s why I liked designing operas, although I enjoyed the music as well.

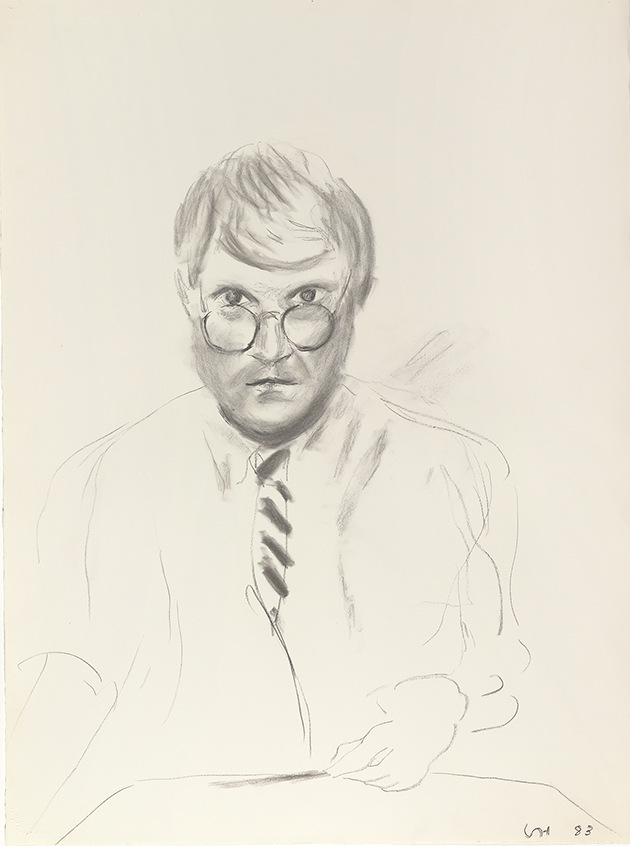

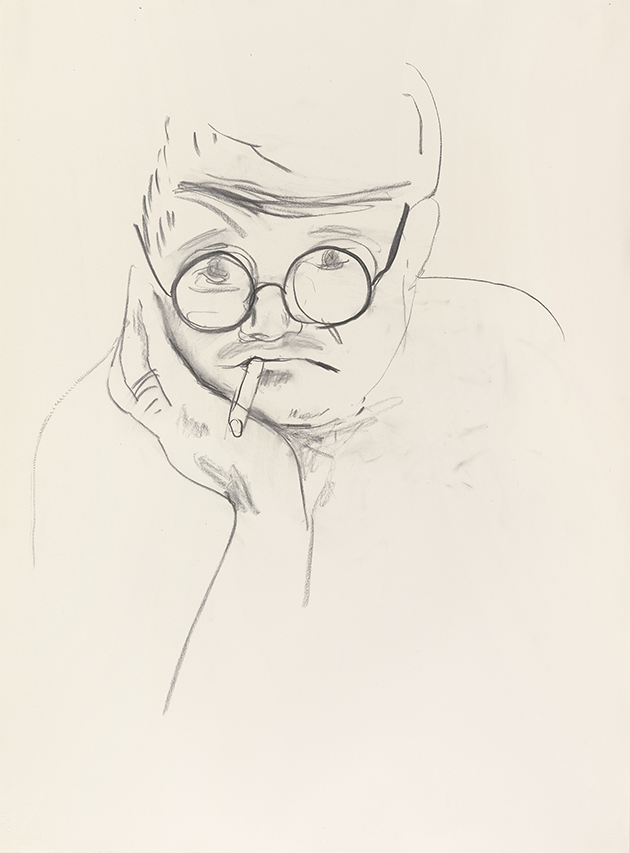

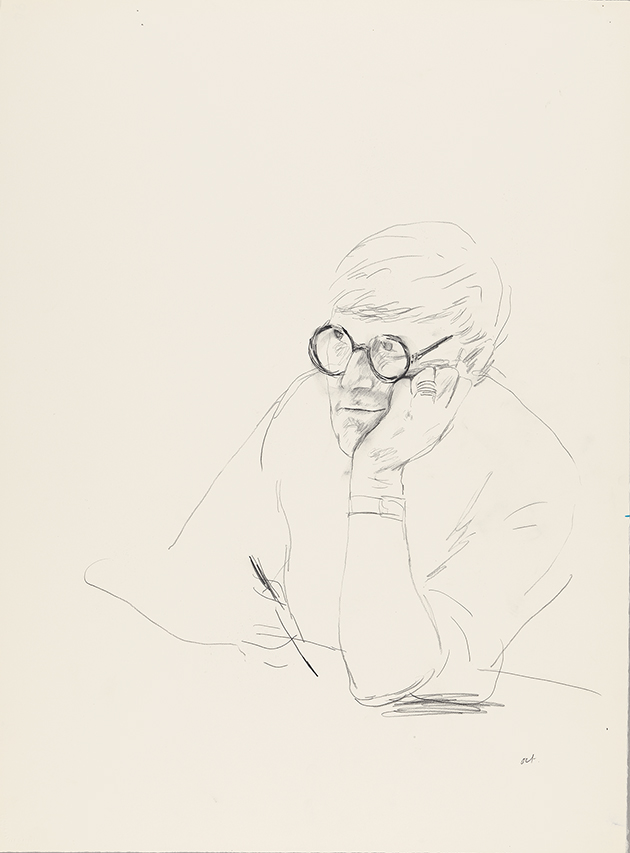

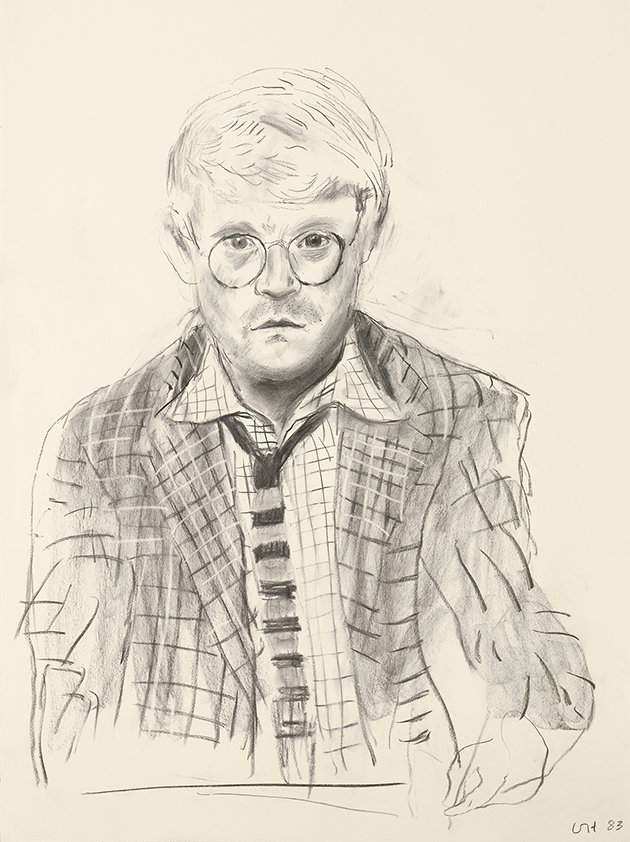

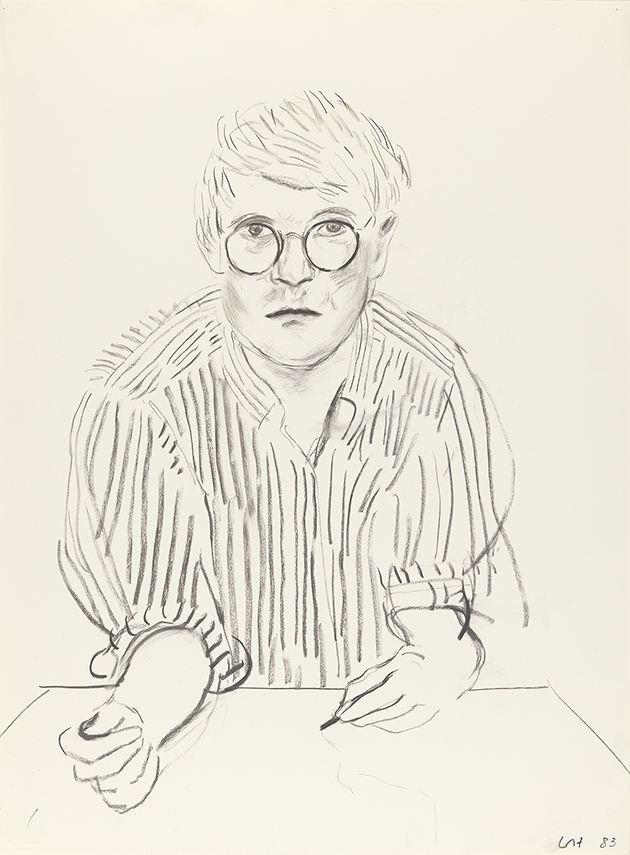

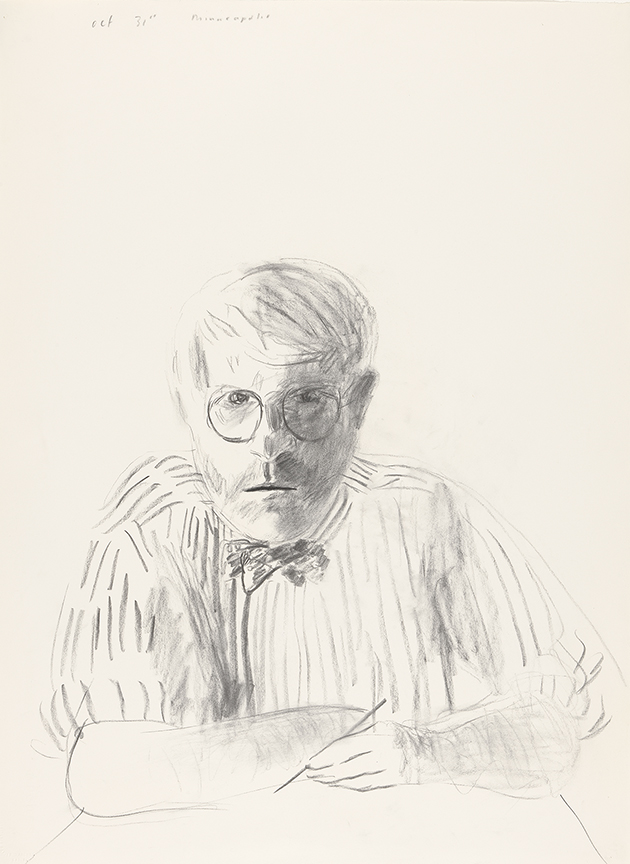

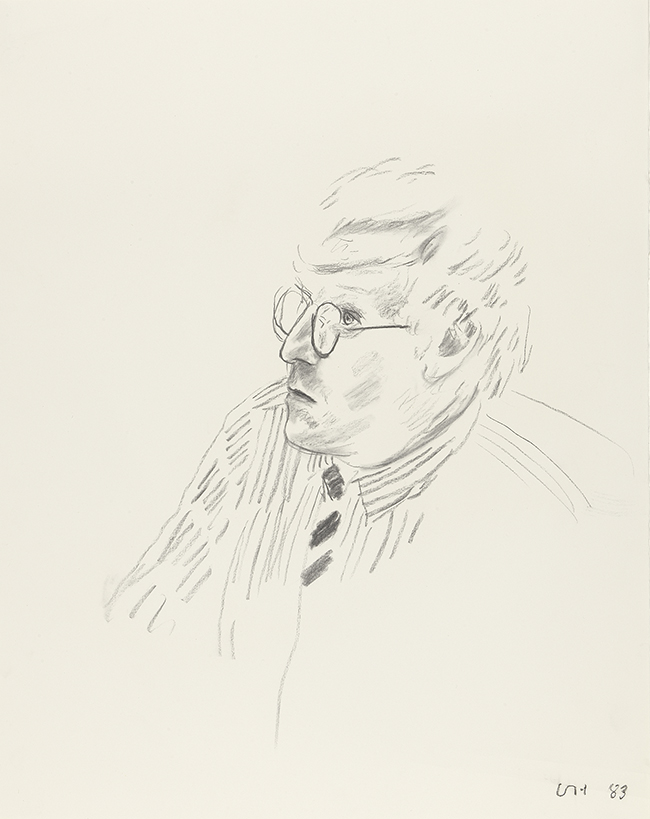

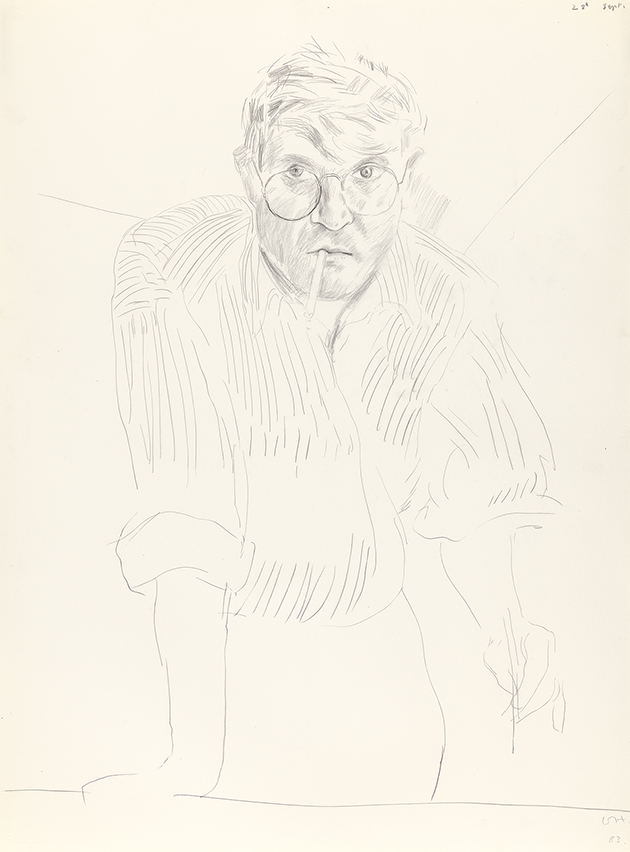

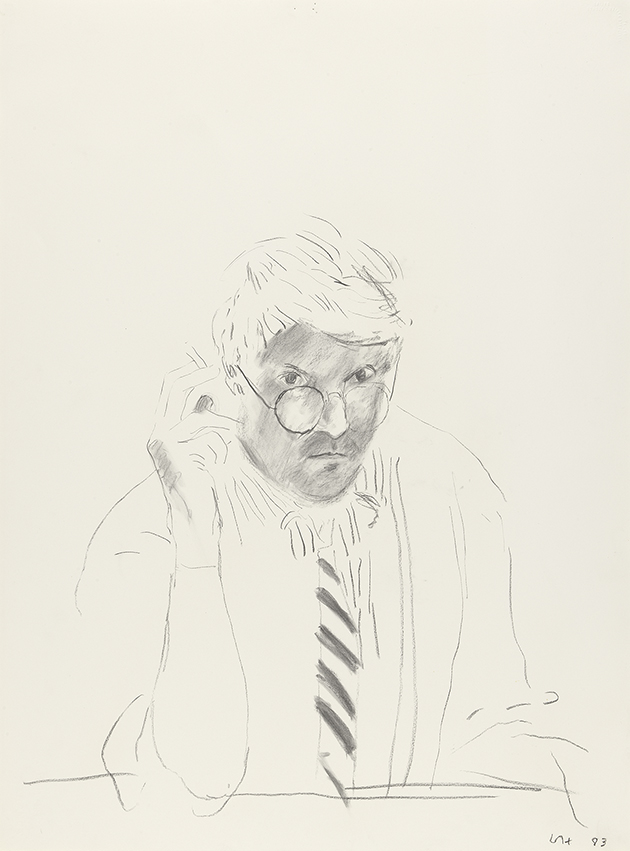

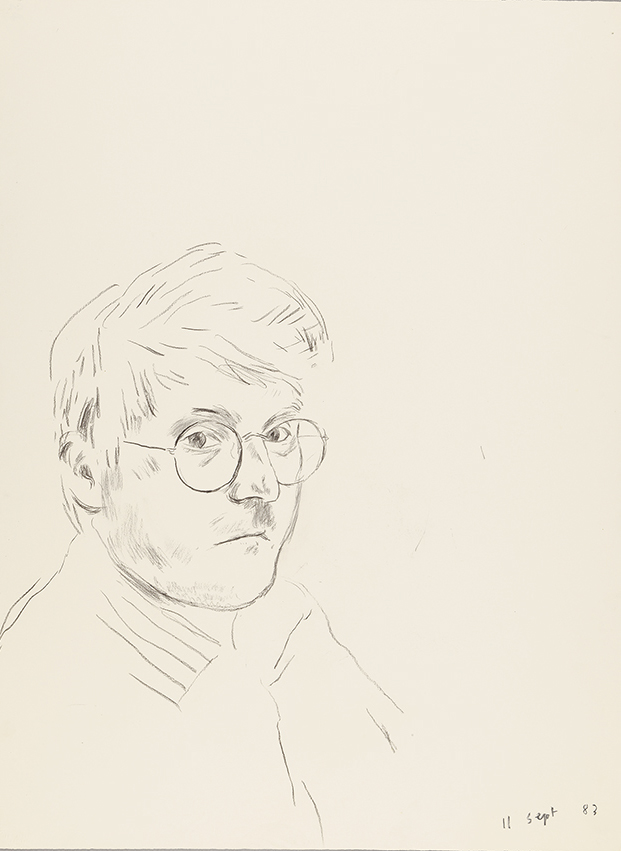

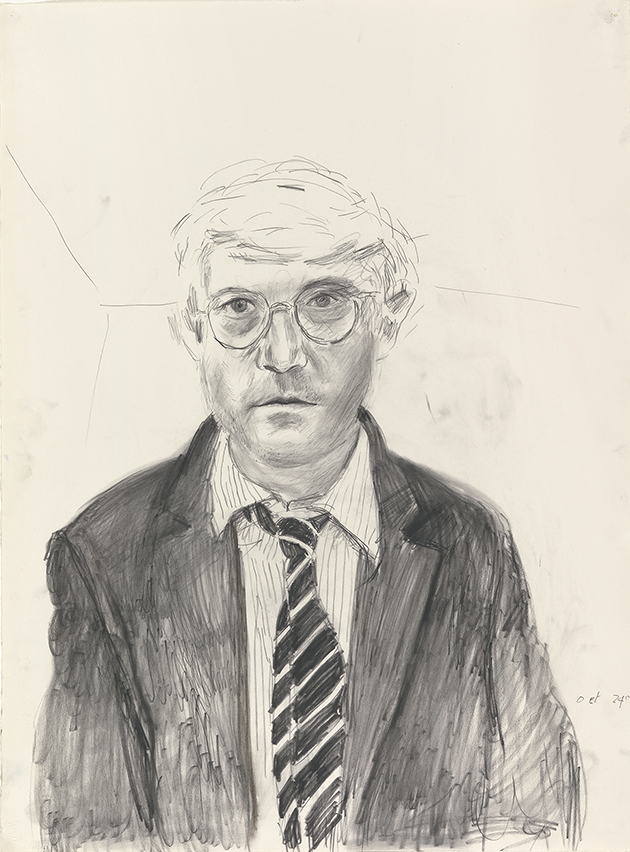

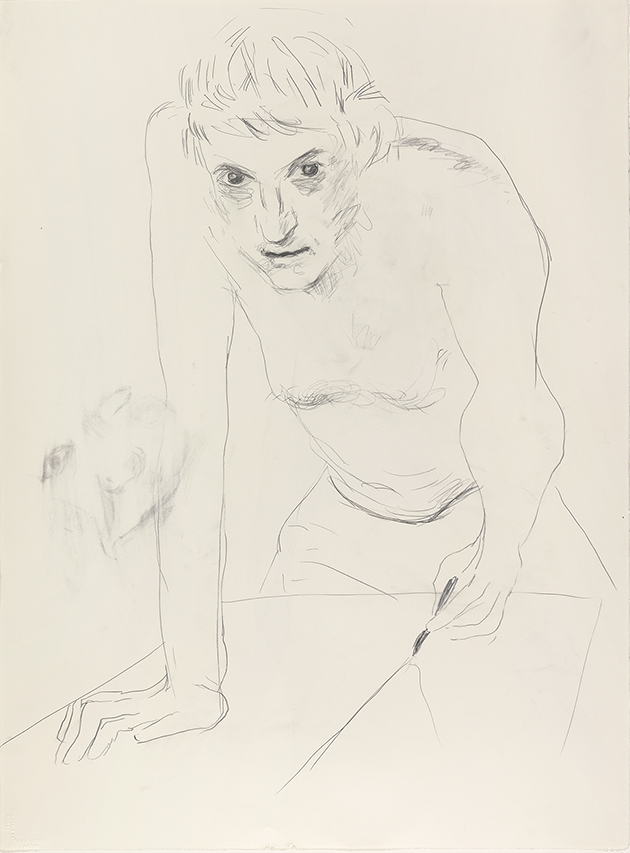

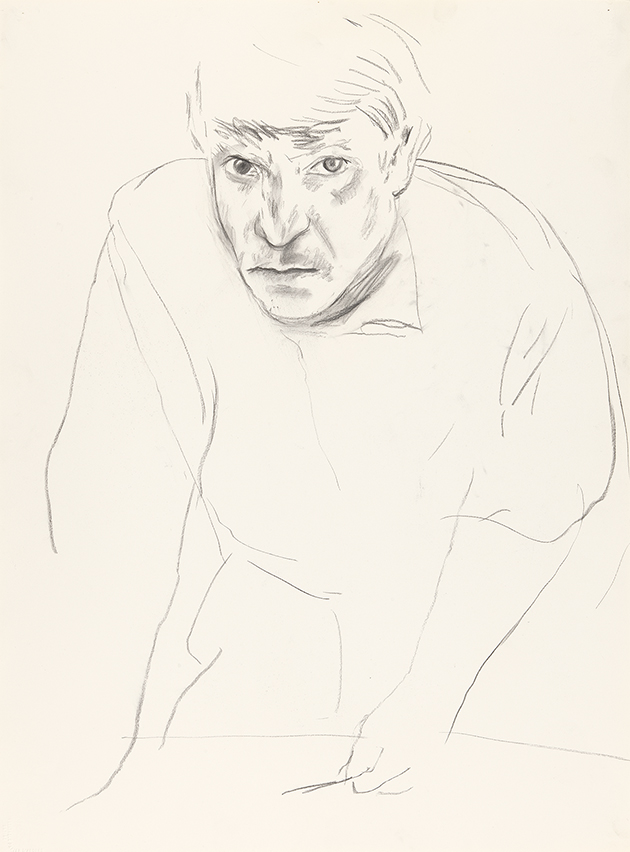

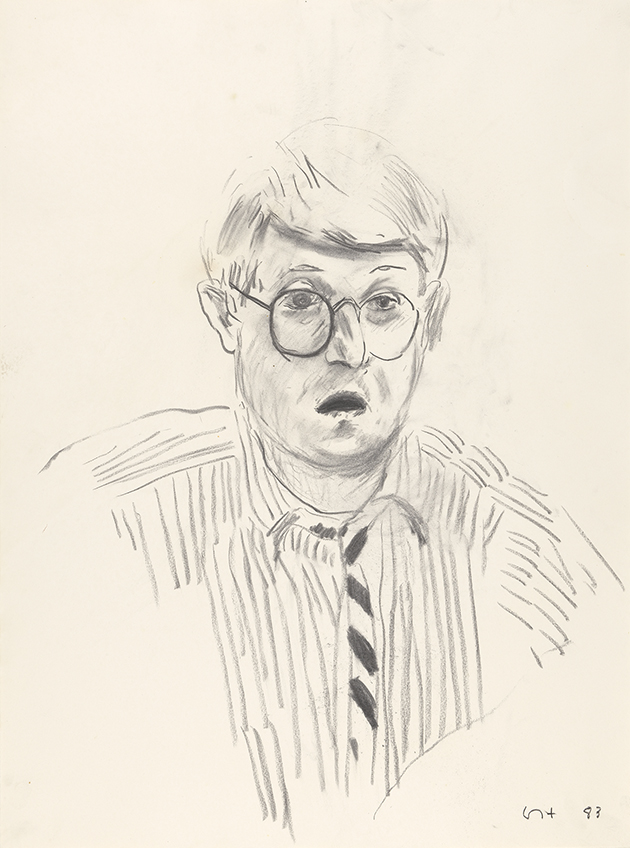

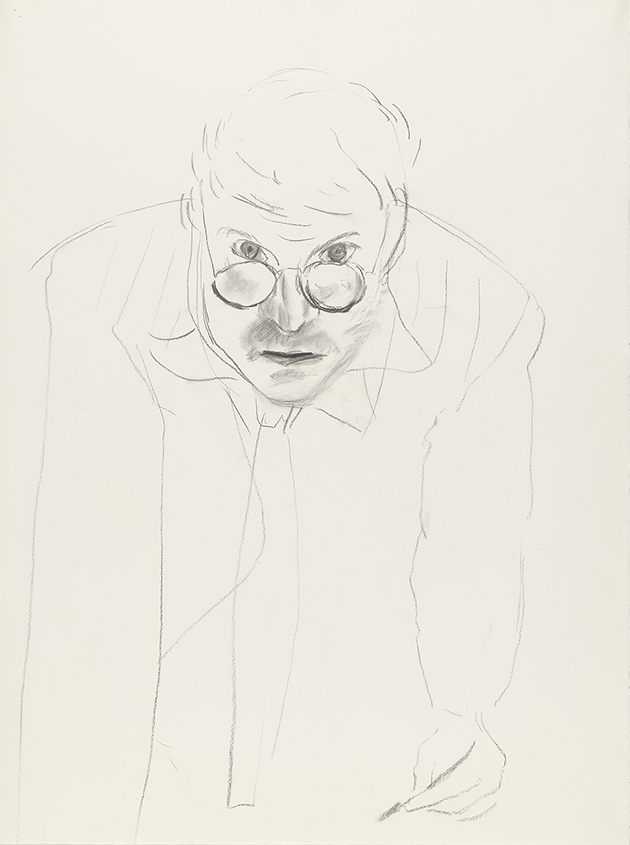

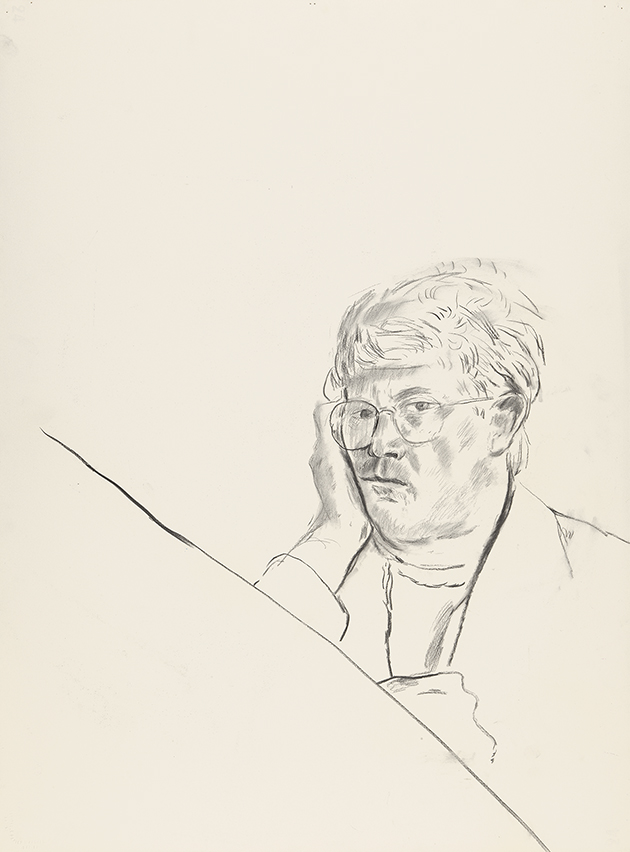

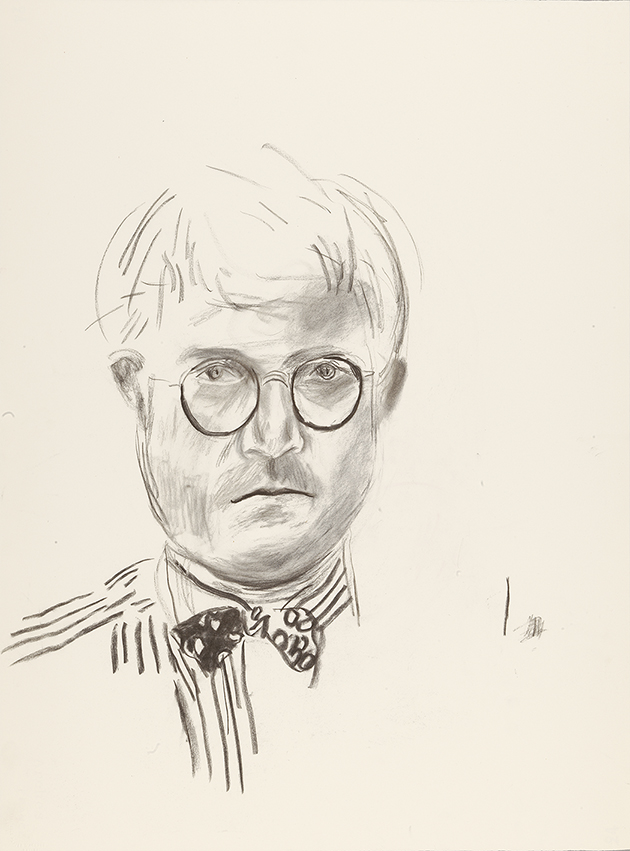

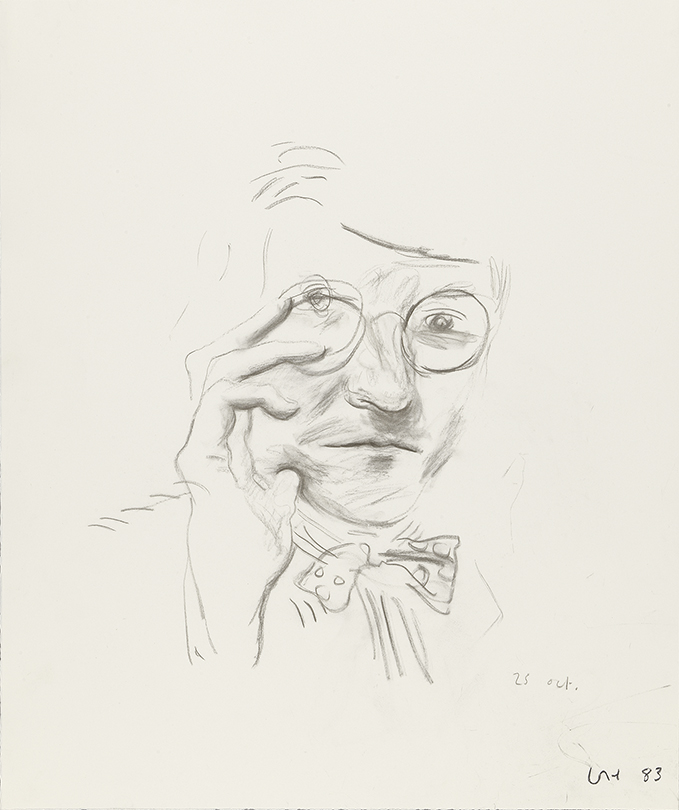

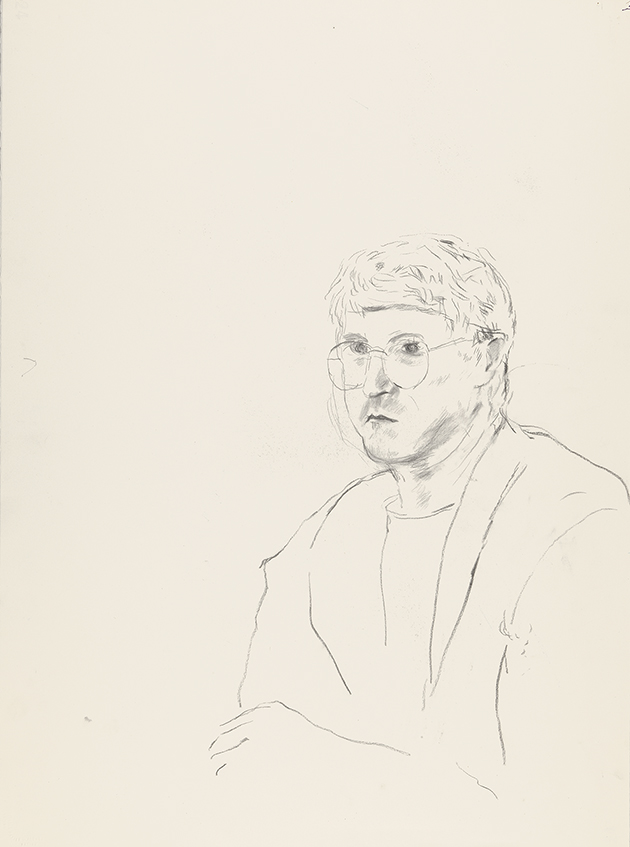

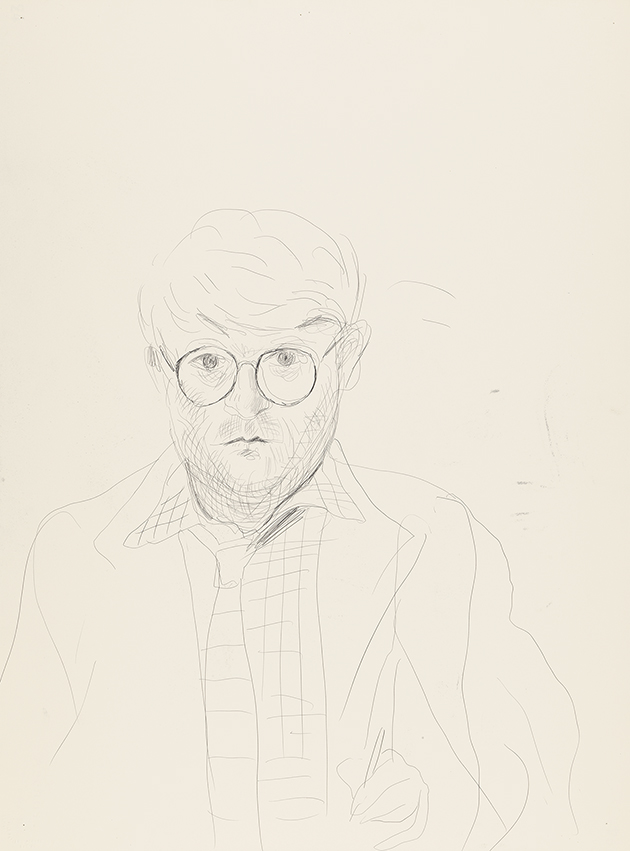

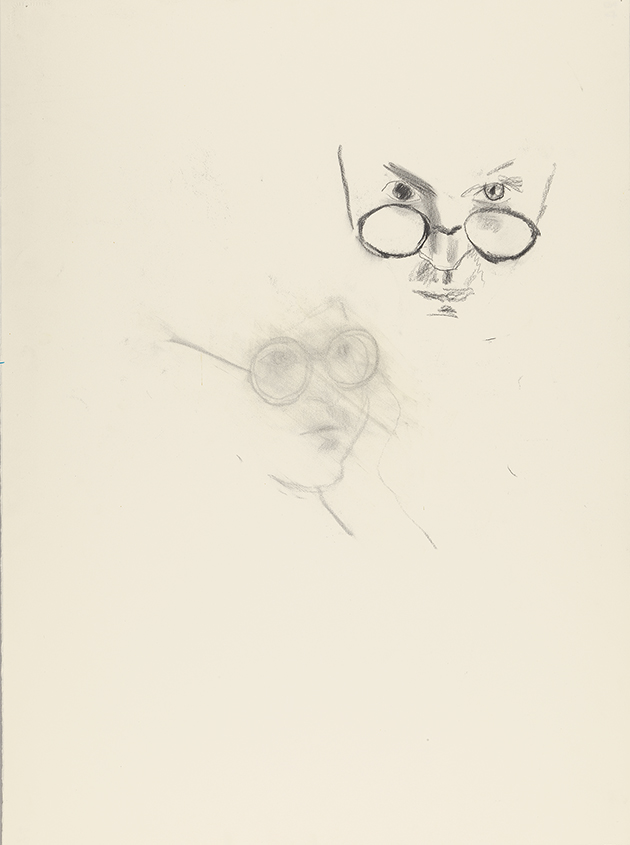

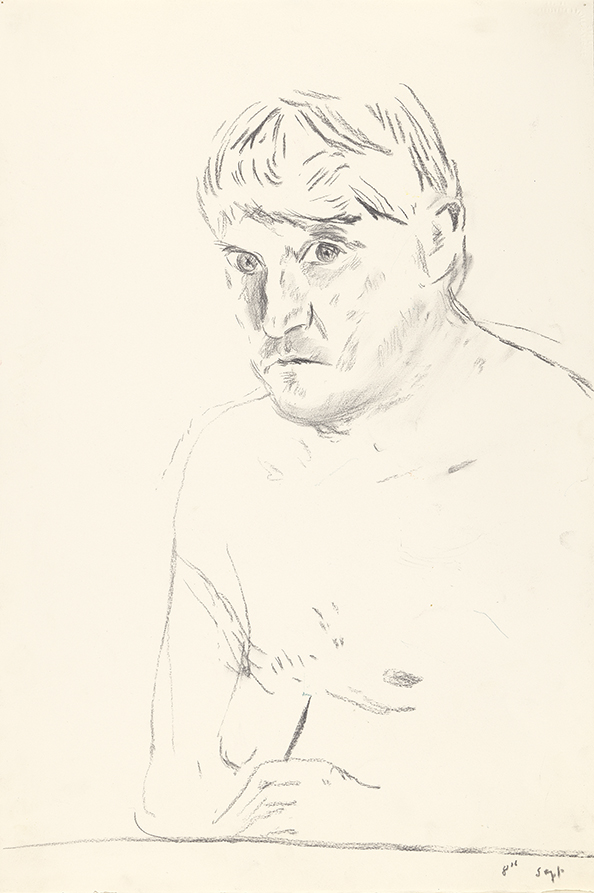

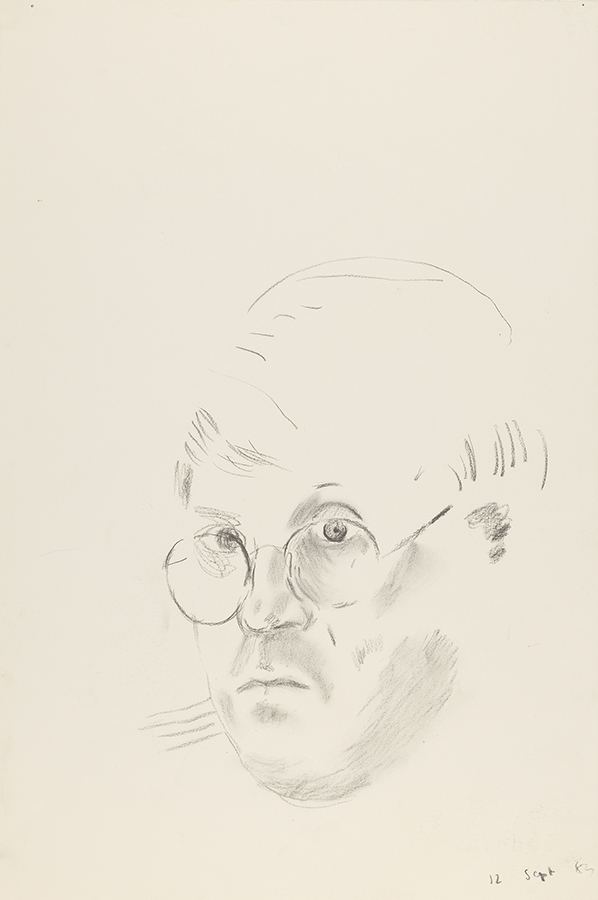

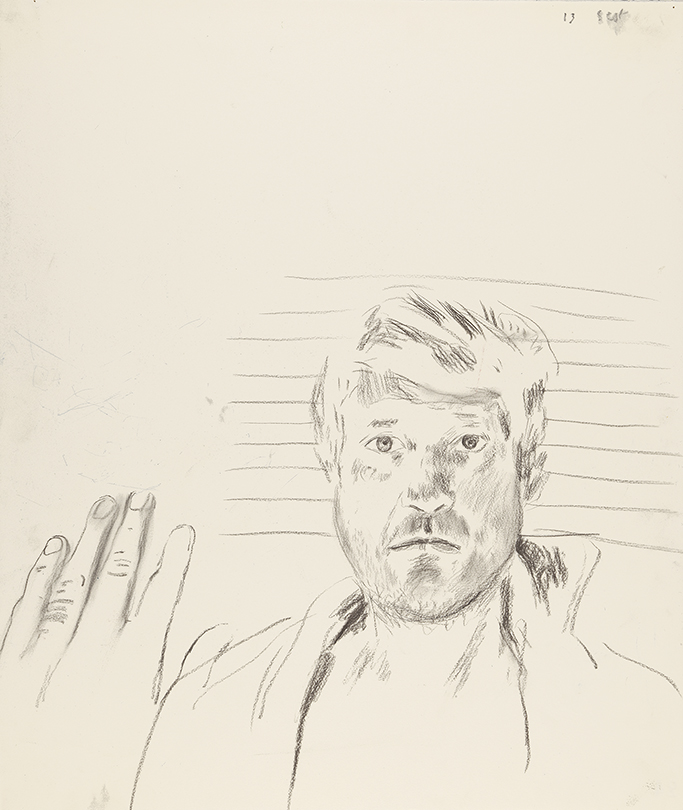

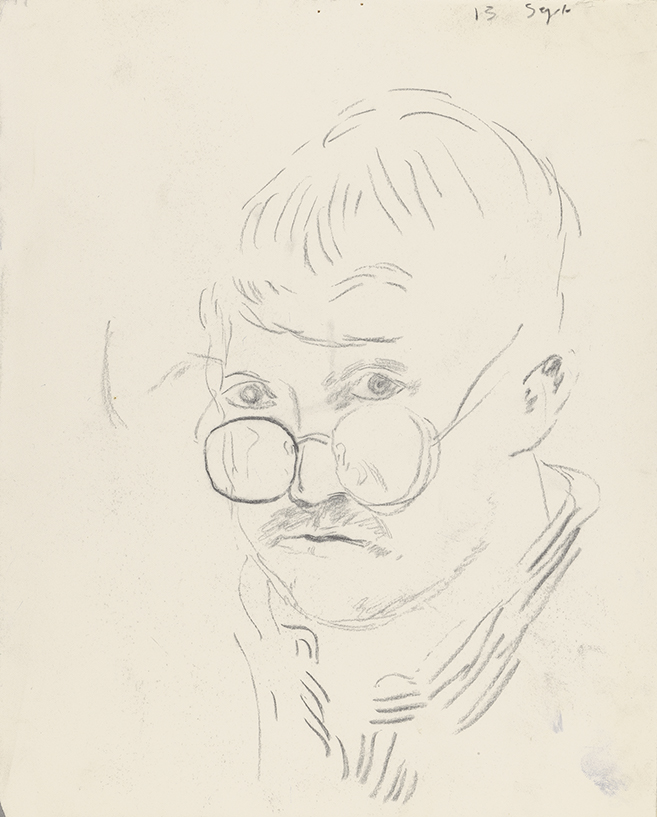

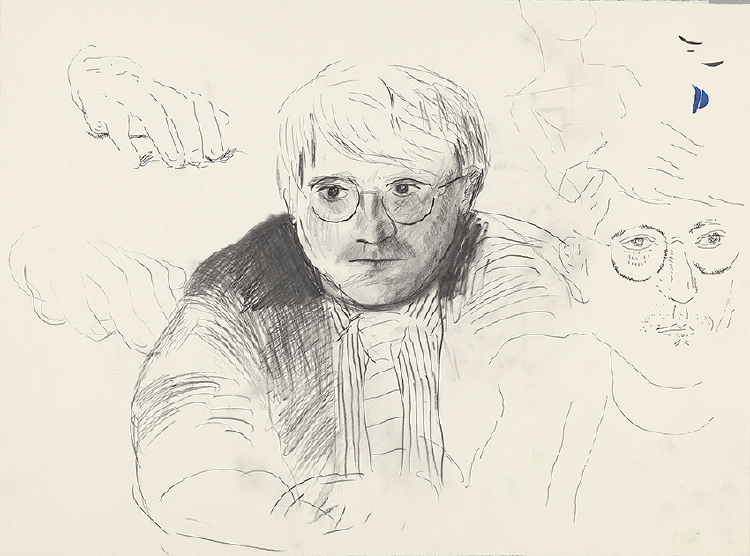

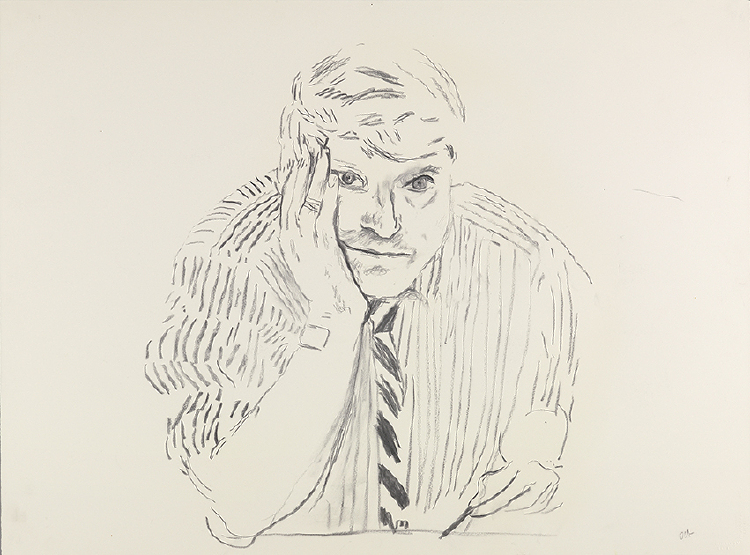

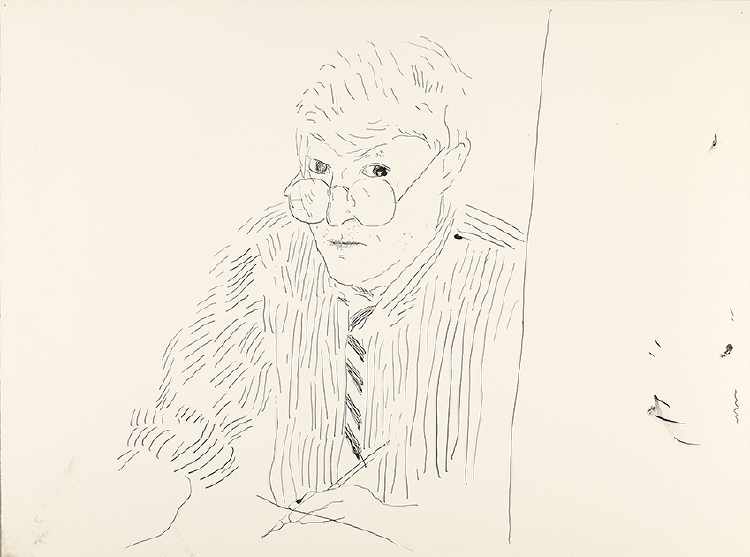

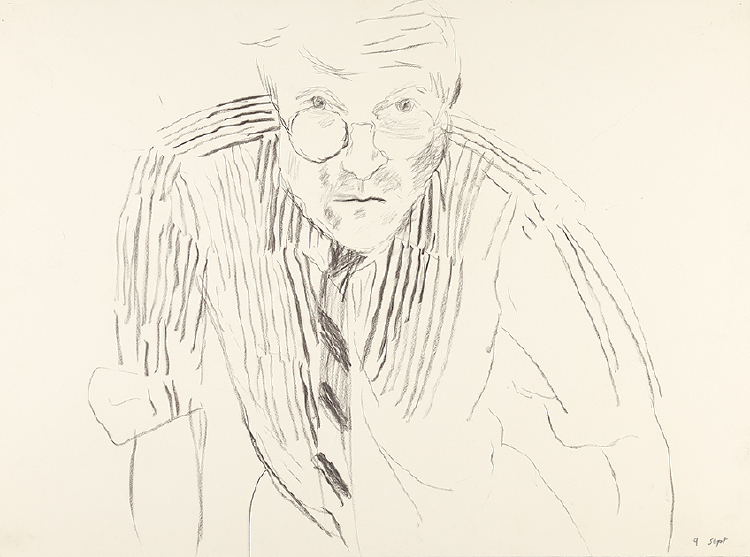

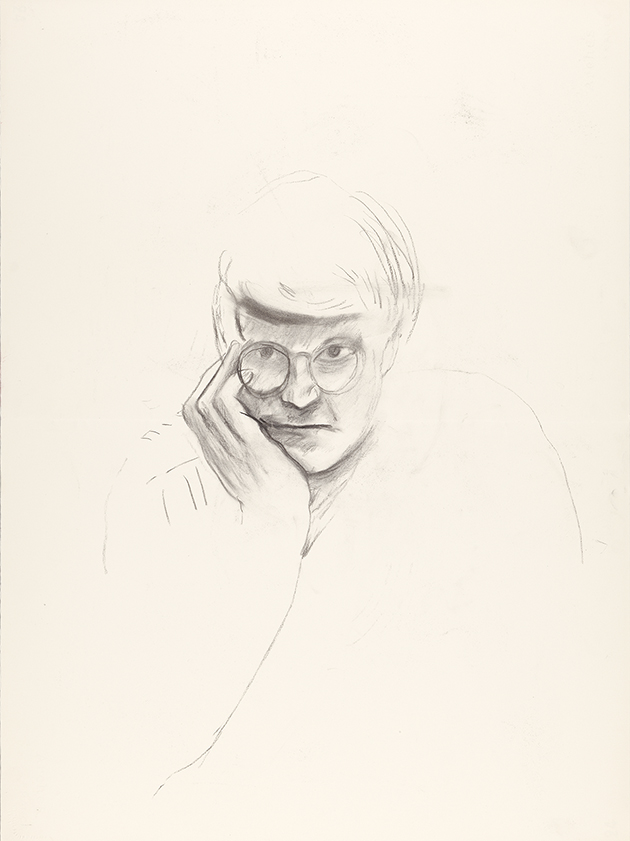

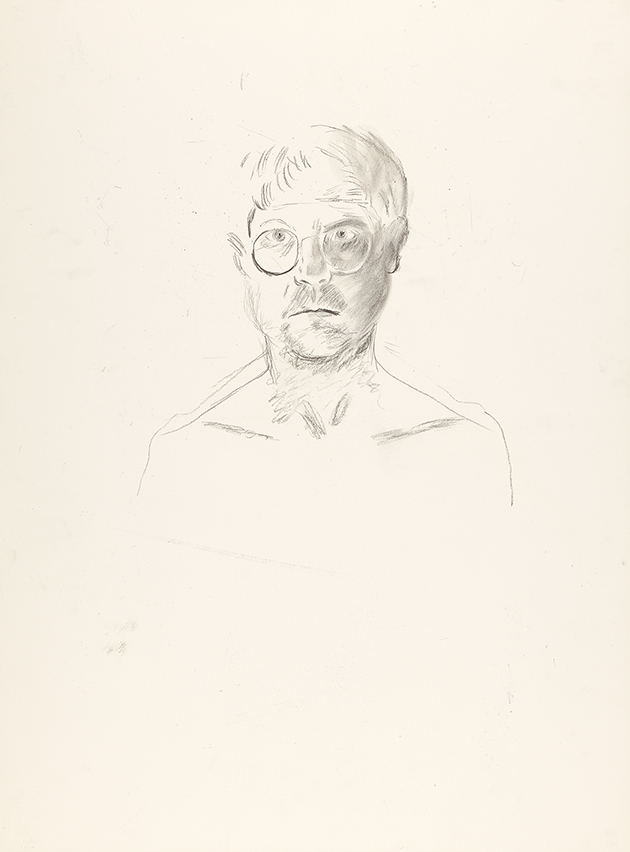

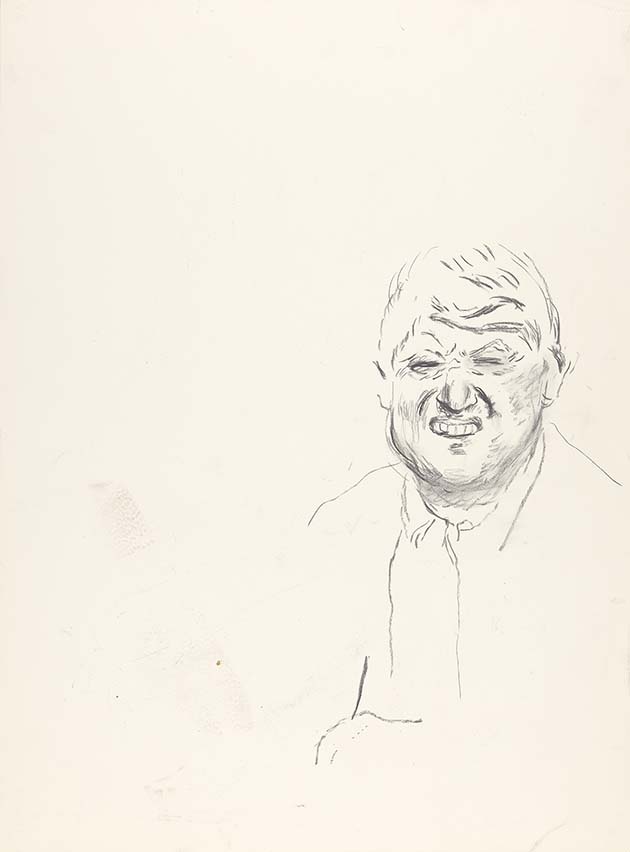

Self portraits

For six weeks in the autumn, Hockney makes scrutinizing self portraits at an unrelenting rate. In Marco Livingstone’s appraisal,[NESTED] “It is curiously comforting to know that even someone with such a sunny disposition sometimes experiences such moods .... What I value above all in these drawings is Hockney’s avowal of our common humanity. His readiness to depict himself with the same honesty and casual forthrightness that has always marked his portrait of others.”

They were drawn mostly early in the morning. I noticed if you did this they were always different: not only did you have different expressions, you also had totally different moods and feelings, and that affects your mind. I realized that your mood is reflected in the way you draw the lines and marks. You also try to pick up the mood of the sitter, so in a portrait of someone else there are two moods. In a self portrait it is the same mood .... The self portraits do reflect the fact that even I was beginning to panic a little bit about the massive amount of work I had taken on.

Exhibitions

Solo

- Drawings for the Theatre, Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo, Japan (Feb 14–Mar 12).

- New Work with a Camera, André Emmerich Gallery, New York, NY, USA (May 7–Jun 3).

- New Work with a Camera, L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, USA (May 14–Jun 25).

- New Work with a Camera, Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA (May 14–Jun 30).

- New Work with a Camera, Knoedler/Kasmin Gallery, London, UK (Jul 5–Aug 30).

- Kasmin’s Hockneys: 45 Drawings, Knoedler/Kasmin Gallery, London, UK (Jul 5–Aug 31); catalogue.

- New Work with a Camera, Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo, Japan (Oct 3–29); catalogue.

- Hockney Paints the Stage, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN, USA (Nov 20, 1983–Jan 22, 1984), travels to Museo Rufino Tamayo, Mexico City (Feb 19–Apr 15); Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (Jun 9–Aug 12); Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (Sep 16–Nov 11); Fort Worth Art Museum, TX (Dec 16, 1984–Feb 17, 1985); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Mar 25–May 26, 1985); and Hayward Gallery, London (Aug 1–Sep 29, 1985); catalogue.

- David Hockney: Posters, Royal Festival Hall, London, UK (Dec 10, 1983–Jan 8, 1984).

Group

- Eight by Eight to Celebrate The Temporary Contemporary, Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, USA (Oct 25–Nov 26).

- American/European Painting and Sculpture Part II, L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, USA (Nov 12–Dec 23).

Publications

Publications

- David Hockney - New Work with a Camera, Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo.

- Kasmin’s Hockneys, Knoedler Gallery, London.

- David Hockney in America, by William L. Beadleston, New York: William Beadleston Inc Gallery.

- Hockney Paints The Stage, by Martin L. Friedman, New York, Minneapolis: Abbeville Press / Walker Art Center.

- David Hockney on Photography, by David Hockney, New York: André Emmerich Gallery.

- Hockney Paints the Stage, by David Hockney, London: Thames & Hudson.

- Hockney’s Photographs, by David Hockney, London.

- David Hockney, by Peter Weiermair, Frankfurt Am Main: Frankfurter Kunstverein.

Film

Film

- David Hockney: Joiner Photographs, 50 min., directed by Don Featherstone.

Honor

Honor

- Honorary Degree at the University of Bradford.